Whenever I return from an expedition, the question I am most frequently asked is "Did you find it?" My most frequently given answer is “I don’t know.” Wreck hunting is a multi-phased approach, where you have a particular technology to complete a certain phase of

the survey. For example, a sonar survey is Phase One, and on a French Navy minehunter it produces images like

this:

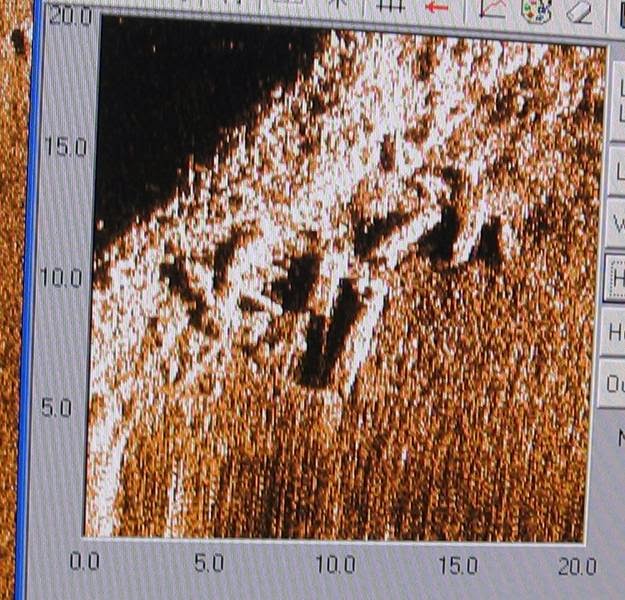

Another kind of sonar produces an image like this:

Is it a wreck or rocks? It's a group of rocks. The two are often so similar that we can’t tell them apart, which brings

us to the next phase: target classification. This is done with either a

ROV, Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) or in some fortunate instances, divers. This image was taken

with a ROV:

Again, is it a piece of a wreck or a rock? If we had divers investigate this object,

could they determine its identity? There

are no guarantees. This image is actually of a concretion, which is a conglomeration of iron objects that become attached to one another when they are in seawater for a long time. We know this only because we used a magnetometer to detect any metal in the object and it gave off a healthy magnetic signature. That can be another phase, but is ideally combined into with a Phase One sonar investigation. When we finally are able to collect enough

definitive evidence about a wreck site, we may be able to say we are onto

something. Until then, we proceed with surveying just in case this wreck is not the one we're after.

Every technological asset we are offered is an expensive gift, and

takes a whole team of people to run it, plus a vessel to support the whole operation.

Try convincing a Navy to mobilize a ship and crew with a number of specific

technologies on board, and you have the makings of a huge challenge. We shoot

for the moon, but are grateful for whatever is offered and available. The saying “Beggars can’t be choosers” is applicable

here, and there is a constant trade-off between what is needed and what is available. So we maximize the

resources we have on each mission, and appreciate them.

So did we find it? I don't know. We may have found it as the wreck site we discovered in 2012, but until we have the right equipment to repeatedly investigate that site and prove its identity, we will keep plugging away. This most recent mission was a Phase One and Phase Two approach, with sonar for target acquisition, and a ROV for a very quick investigation of a single target. Phase Three would be to put divers down on any new sonar targets, including our priority wreck site. Stay tuned for that, it just may happen!

So did we find it? I don't know. We may have found it as the wreck site we discovered in 2012, but until we have the right equipment to repeatedly investigate that site and prove its identity, we will keep plugging away. This most recent mission was a Phase One and Phase Two approach, with sonar for target acquisition, and a ROV for a very quick investigation of a single target. Phase Three would be to put divers down on any new sonar targets, including our priority wreck site. Stay tuned for that, it just may happen!